Shakuhachi traditionally has its own notation system, written in Japanese from top to bottom, left to right. It is surprisingly easy to learn to read, and benefits from being designed specifically for shakuhachi (in Japan each instrument has its own unique notation system) so that it is extremely efficient and expressive.

Tone Colour

Whereas in regular staff notation (the notation system used in Western music), two notes of the same pitch but different tone colour, or timbre, might be written with the same symbol (and thus not differentiated), in shakuhachi notation they will be given entirely different symbols. Since tone colour is fundamentally important to shakuhachi music, and since one of the shakuhachi’s most distinctive atributes is its flexibility and breadth of tone colour, this is an essential characteristic of the notation.

Rhythm

There are in fact several different shakuhachi notation systems, depending on the region or school (see more below), and rhythm is expressed in different ways depending on the system. In the older schools for which honkyoku was the main, or sometimes only repertoire, the expression of rhythm may appear ‘imprecise’. For example, the ‘taco ashi’ (literally ‘octopus legs’) in the old Seien Ryu scores do not have definite value, but are read through their varying length in an analogue fashion. And it it this analogue quality which is in fact so important.

The honkyoku are generally not rhythmical. They are sometimes described as having ‘free rhythm’. This does not mean they have no rhythm, that they have no beat. The timing must therefore be internalized. Through learning the music from ones teacher, one ingests the very meaning of the music – and this meaning is the music itself. This may sound abstract, but in fact is not at all. Once ingested, one understands where to play long, where to play short, and the individual nuance of each phrase, which includes also the possibilities and limitations of how flexible one can be with that timing. This cannot be read directly from the notation, but reading the notation works together with study from ones teacher, so that having studied the piece, the notation becomes clear. The interesting point in this is that if this music is written in a notation system which does define rhythm precisely, much is actually lost! The more ‘imprecise’ analogue way of writing is actually much closer to the way the honkyoku naturally exist, enabling a more direct and precise oral transmission of the music. By defining the pitch precisely in the notation, an entire dimension is stripped away. One common danger from this is that the music can become rhythmical in the sense of having a defined beat, and be generally reduced in musicality.

In the more modern notation styles, rhythm is written precisely, and so is comparable with staff notation. This is especially useful for ensemble music and modern compositions. Kinko Ryu developed precise notation at the beginning of the 20th century with dots on the left and right representing the rhythm of the shamisen and koto music which they were accompanying. This was first published in the scores of the Grandmaster Araki Kodo III and is now used is all Kinko Ryu scores.

More modern developments include systems adapted to shakuhachi notation based on representations of rhythm found in staff notation, such as Tozan Ryu and Chikuho Ryu. The precision of these systems was particularly important for the more complex rhythms found in these schools, which primarily focused on the new music being created in Japan from Western and Japanese elements.

Regional Notation Styles

Nowadays the most popular shakuhachi school, and therefore notation, is that of Tozan Ryu. This school was created in Osaka after the abolition of the Fuke sect, and since it has none of the religious honkyoku music in its repertoire, is not covered by this website. The next most popular school is Kinko Ryu, followed by Taizan Ryu and its derivatives.

There also exist some notation styles rarely seen nowadays. Seien Ryu has its own system (on which Taizan Ryu is based), as do Kimpu Ryu and Myoan Shimpo Ryu.

Contemporary shakuhachi schools generally use only one notation system to notate all of their honkyoku, even if the pieces in their repertoire are collected from various other schools. Since Justin learned Kimpu Ryu, Kinko Ryu, Myoan Shimpo Ryu, Seien Ryu and Taizan Ryu each in their own unique notation systems, he gives the option for students to learn each style in their native systems. This can help to preserve nuance, and helps to connect us to the heritage and history of each individual school.

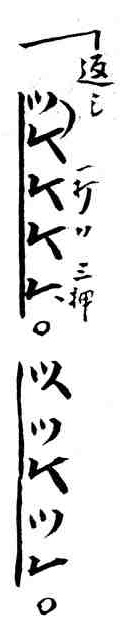

On the left you can see samples from the four main forms of notation Justin uses and teaches with.

With Myoan Shimpo Ryu in particular, Justin has been asked specifically by his teacher to refrain from translating the music to a more common notation style and to teach only using the ancient ‘fu ho u’ notation system of Kyoto Myoanji. Once widespread, this music is now extremely rare. It has been taught in its traditional notation system from generation to generation up to today, when it continues to be transmitted by only two teachers, Justin and his teacher Otsubo Shido. Keen to preserve this tradition, Otsubo has requested Justin to continue teaching the Myoan honkyoku in its native notation out of respect to those masters from whom we received it, and so as to preserve its delicate, unique nuance and atmosphere.

See this page for information on shakuhachi keys, tuning, temperament and scales.