This page discusses the tuning, keys, scale and temperament of traditional shakuhachi music. If you would like to skip ahead to listen to each key, taking ロas D, you will find recordings on an Edo period jinashi shakuhachi at the ‘Listen to each key‘ section of the page. Some of the following with be straightforward, some will be quite detailed on the topic of microtonality. So don’t worry if only some of the following speaks to you.

Contents:

- One scale, two halves

- Key Change

- Issues with Banshiki Chōshi

- チ大カ and the historical placement of the 3rd hole

- The Four Units of Insempō

- Listen to each key

For the benefit of temperament lovers: - Temperament

- A new temperament for old music – Senryū I Insempō Temperament

- Key Changes – Complete temperament

- Error rate across keys (for microtonality fans).

One scale, two halves

Shakuhachi honkyoku of the Edo period used the scale known as insempō. I will explain how I perceive this scale, as I have experienced it phenomenologically from my study and practice of Edo period shakuhachi honkyoku and ensemble music.

The scale is composed of seven notes. There are five notes which are dominant, and two more ‘secondary’ notes, one which seems to me specifically in shakuhachi music as being more ‘important’ (more used) than the other. Furthermore, the ‘notes’ have two aspects, both of critical significance. They are, pitch; and tone colour. We can consider there to be two tone colours, ‘dark’, and ‘bright’. The dark notes are produced by a technique known as ‘meri’, which involved manipulation of the embouchure, and for some of them, some amount of finger shading. This means that there can be two entirely different notes which may share the same pitch, since both factors need to be shared for it to be considered the same note. However, in fact, the meri notes bare a specific microtonality, usually considered to be roughly 25 cents flatter than their nearest Western (i.e. 12 tone equal temperament). So they have both a different tone colour, and this slight difference from the Western temperament. The bright notes are known as ‘kari’ notes. This refers to the standard, non-meri embouchure and position.

This scale is played in a number of different scales. I will discuss the others below, but now less us go into more detail, using Akebono Chōshi as an example.

I will be using the shakuhachi note symbol system of Seien Ryū (shared by the Taizan Ryū schools (‘Myōan Taizan Ha etc.) also), to talk about the different notes. If you are a Kinko notation reader, the only difference here is that リ and ヒ are both written as ハ.

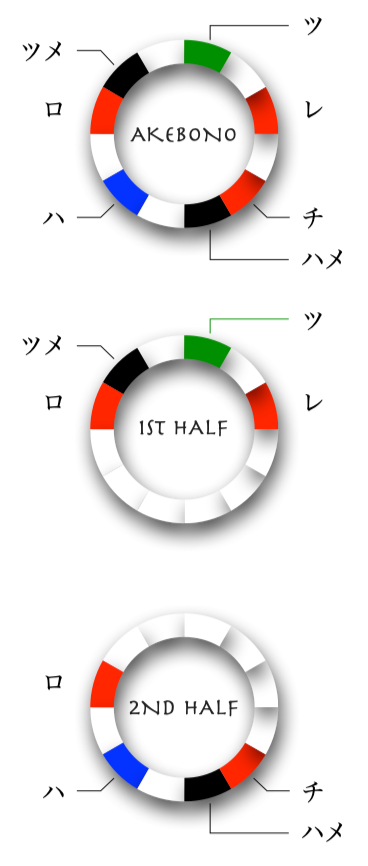

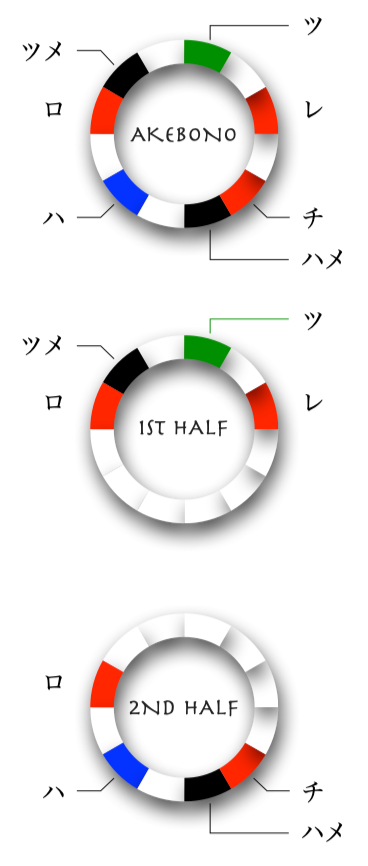

There is a natural relationship of the first half of the insempō scale, ロ ツメ ツ レ); to the second half, チ ハメ ハ ロ. The first and second half of the scale are phenomenologically speaking, a reflection of each other, and thus it will be musically pleasing if the two halves are as close as possible to each other. And I tend to find visualising the notes of a key in a circle rather than a column, since as one continues going up the octaves, the same notes return – the circle is really a two dimensional cross-section of a spiral, as the notes return each time at a higher octave. So here is a visual representation of this key, and its two composite halves. I will also use colour to display more of the qualities the notes embody. I’ll use blue for the main secondary note (which is kari notes, and which I will discuss further below); red for the primary kari notes; and black for the meri notes, since their tone colour is dark. This is important when considering key transposition for shakuhachi, since this scale is not merely defined by pitch, but also by tone colour, differentiating between light and dark notes. Thus, the transposed key should maintain both correct pitch and appropriate tone colour for each note.

N.B. チメhas a standard pitch, whereas ウ has two main pitches, those being the pitch of チメ and the pitch レ. To keep things simple, I have used チメ in this discussion. Bear in mind that in many cases that will in practice be substituted with ウ, in which case it will have the same チメ pitch, and both of them have dark tone colours.

ウ is used also at the same pitch as レ in Hon Chōshi in some schools of honkyoku, which breaks the strict rules of light and dark in tone colour, but show that these rules are not as strictly followed in honkyoku as they are in ensemble music. Sometimes this deliberate use of alternative tone colours in used to enhance the tonal variations in the music, most notably in Kimpū Ryū, though we will leave that for another discussion.

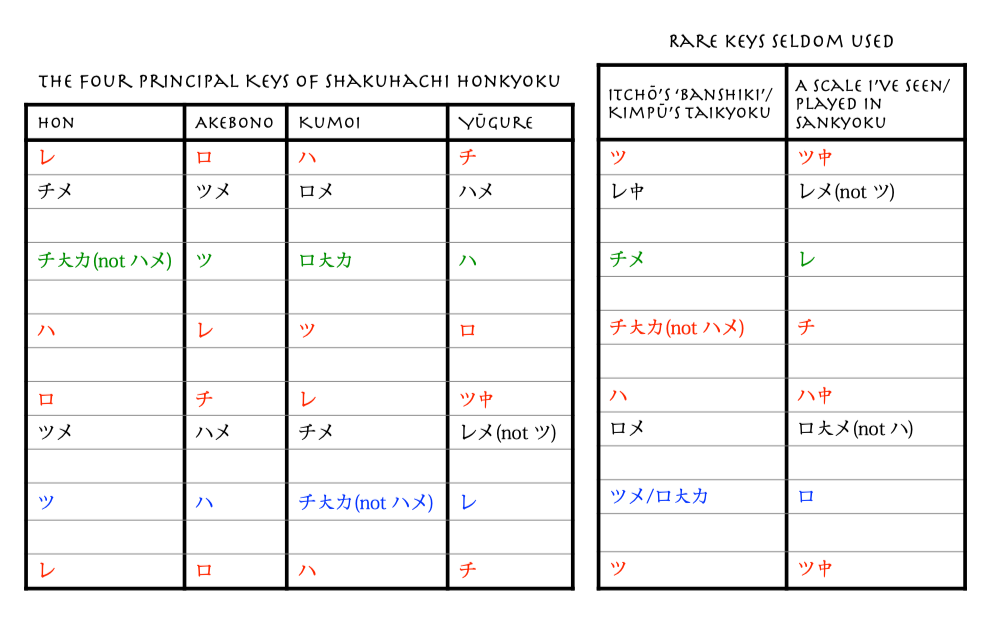

Key Change

The next thing to consider is the principle of key change. In Akebono Chōshi, the ‘home note’ is ロ. The most common key is in fact Hon Chōshi, with the home note being レ. A third used from time to time is Kumoi with the home note of ハ. Other keys are used only rarely in the shakuhachi honkyoku repertoire, though they are not limited to ensemble playing – Kichiku Ryū honkyoku does use Yūgure Chōshi (home note チ) for example, so we will also consider that. There is also a fifth chōshi spoken of in Kimpū Ryū, Taikyoku Chōshi, said to have the home note as ツ, but I have never heard it (or even heard of it) performed, though it does feature in rare version of Sugagaki in Yoshida Itchō’s notation, where it is referred to as Banshiki rather than Taikyoku. I have come across a key with the home note being ツ中メ, but I’ve never seen that in honkyoku either, and only rarely in ensemble music.

Here is a chart of these keys, in which you can see by the columns, where these notes lie relative to the twelve note octave system, though remember some of the intervals are microtonal.

Issues with Banshiki Chōshi

You may also notice Banshiki has チメ and also ツメ/ロ大カ, where there should be kari notes. チメ will at least be brighter than using ウ – not ‘perfect’ but the only reasonable solution, and t least should be played with a higher pitch, such as around Ab -5 cents. Similarly レ中 will need to be flattened, let’s say F# -73c.

ロ大カ should be favoured over ツメ but is too difficult for many in the lower octave, so ツメ may be used, but at the pitch of ロ大カ. In the upper octave, the 5th or 4th and 5th holes may be opened to sharpen ロ up enough to a good ロ大カ – this technique is quite easy and gives a lovely bright sound. These issues may help to explain why this key is so rarely used. To keep things simple and since they are so rare, I will not include this nor the last key (which requires additionally ハ中 and ロ大メ) in the complete temperament below.

So this gives us a total of 13 notes in the octave when the 4 main keys.

チ大カ and the historical placement of the 3rd hole

チ大カ is a note which almost never features in the honkyoku of contemporary schools, one exception being in Kumoi Jishi, which entered into the Chikuyūsha branch of Kinko Ryū around one hundred or so years ago. That we could talk about here, but to keep this brief, I will talk about that elsewhere. However, it was commonly used in the Edo period Kyōto honkyoku (Kichiku Ryū – very few of us still teach this style), and is common in the ensemble repertoire. However even in that ensemble music, it is generally replaced today with ハメ. This may seem strange since it ハメ is the wrong tone colour, being dark when it should be light – it is specifically used as the 7th (green) note in Hon Chōshi. So why, you may ask, has it for the most part been replaced?

There is another common question about チ, the answer of which is intimately connected to the above. And that is, ‘Why are Edo period flutes tuned with a higher pitched 3rd hole, giving a sharper チ than today’s shakuhachi?’

Some answer this by attributing it purely to ascetics. The 4 holes on the front of the shakuhachi were, until the time of Araki Kodō II’s students, evenly spaced. Araki Kodō II, usually known by his retirement name Chikuō, and often said to be the greatest shakuhachi maker of all time; the last head of the main Fuke temple, Ichigetsu-ji; and the head of Kinko Ryū, was said to be the first person to even make the hole smaller (without moving it), and there was quite a backlash – even this caused a stir! He did it to better tune to strings for ensemble playing, it is said. Here are images of an Edo

So there is some reasoning behind this idea of resistance to changing aesthetics, at the cost of pitch. However, I have a different proposal. Though, this does not necessarily go to say that aesthetics played no part.

I have been fortunate to have studied ensemble playing in depth with Araki Kodō V. He is one of few players who still teaches to use チ大カ, rather than habitually replacing it with ハメ. I’ve also been fortunate to own a number of fine Edo period shakuhachi; and, I teach the ancient Kichiku Ryū repertoire, which makes extensive use of チ大カ in honkyoku. And I can say that it is far easier to play チ大カ with these shakuhachi, than with modern-tuned shakuhachi. The technique for producing the extra ‘kari’ necessary to attain the higher pitch while retaining チ fingering, is difficult. And the amount one is able to push the pitch upwards, is limited by the original pitch of チ.

Let me explain. From the finger position of チ, one has to access three different notes, all of different pitches:

- チ大カ

- チ

- チメ

On the modern shakuhachi, played in the standard position, one produces チ. チメ is easily accessible. But チ大カ is beyond the limit of most players, the resulting attempt being too flat. On the Edo period shakuhachi by contrast, in the standard position, an out of tune, sharp チ is produced. This is why they are thought of as (rather badly) ‘out of tune’. However, because the standard position is that sharp, being somewhere in between the pitch of チ and the pitch of チ大カ, チ大カ is accessible to the player. And meri being far easier than ‘extra kari’, the チ and チメ are also readily accessible. This seems to me a very good reason for the tuning of that 3rd hole. And indeed just last week, I performed a version of Rokudan along with koto in Prague, from notation written by a famous komusō, Ikeda Isshi (see him on the Kinko Ryū lineage chart here), in around 1772. I chose to play the piece on an Edo period shakuhachi (made by Kanshi, a student of Kurosawa Kinko III) partly to give an authentic sound for this period performance, but also because it was far easier to play the piece in tune due to the use in the piece of チ大カ.

It’s hard to see perhaps, but here is a photograph of the Edo period jinashi shakuhachi I mentioned above from my performance, with the old hole system, followed by a 1.8 made by Chikuō – he is said to be the first person to develop the use of ji (a paste of clay powder and urushi used narrow the air column inside the bore) in shakuhachi, in the style that is now known as ‘ji mori’ – minimal ji. However he only used any ji if he needed to. In this 1.8 there is no ji at all, so we call it ‘jinashi’. The holes on the front are still equally spaced, as with the Edo period shakuhachi; but the 3rd hole is smaller.

Chikuō’s students were the first to extend Chikuō’s use of ji in creating what is often called ‘ji ari’, in which the entire inner surface is coated in ji and carefully shaped. Almost all modern shakuhachi are made using this method. The maker generally said to have been the best maker of this style, was Chikuō’s son Araki Kodō III. His 1.8 is the next picture. The 3rd hole is smaller than the others, and now with a lower position. These changes can also be seen among the shakuhachi of other makers among Chikuō’s students, such as the highly acclaimed Miura Kindō.

The last image is of a 1.7 which I made, in the making style of Kodo III. My 3rd hole is slightly lower still compared to Kodo III’s system, allowing for accurate pitch while not needing to make the hole quite so much smaller than the other holes, as is common with modern shakuhachi. So it has taken time from Chikuō, who died in 1908, to come in the last several decades, to this position, and it still varies somewhat from maker to maker, co-relating distance with the hole size variable.

The Four Units of Insempō

The ideal of a whole scale is not really present in this music. So let’s think about how the notes are used in the music. We are usually using specific sets of notes, in specific contexts. You can think of this in terms of each half of the scale, as I showed Akebono Chōshi in two halves. See again:

Within each half, we have the two primary kari notes, in red. These will be used in both options. The variation comes in choosing whether to complete the set of three with the secondary kari note, or the meri note. Basically, a black note can be swapped out for a blue/green note. So we have these options:

1st half:

ロ ツメ レ

ロ ツ レ

2nd half:

チ ハメ ロ

チ ハ ロ

These four are the basic building blocks of the music, so it may be better to think of these as the most fundamental elements, rather than forcing a concept of ‘scale’ onto the situation. Koizumi, a Japanese music scholar, may be on the same page as me here perhaps. As Alison McQueen Tokita explains:

“Koizumi called this phenomenon one kind of “modulation,” as he saw this combination of two different tetrachords as systematically different from scales which resulted from the doubling of identical tetrachords.”

‘Mode and Scale, Modulation and Tuning in Japanese Shamisen Music: The Case of Kiyomoto Narrative’, Alison McQueen Tokita, Ethnomusicology, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Winter, 1996), pp. 12

You may assume that when combined, these would always be used as either:

ロ ツメ レ チ ハメ ロ

or;

ロ ツ レ チ ハ ロ

However reality is not so simple. In shakuhachi music, the most common ‘scale’ used with ascending melodies, is an asymmetrical choice. In Hon Chōshi the most common ascending scale is:

レ チメ ハ ロ ツ レ

レ ツメ ロ ハ チメ レ

Akebono’s equivalent would be:

ロ ツメ レ チ ハ ロ

ロ ハメ チ レ ツメ ロ

While these are the most common, in practice, the music works more fluidly choosing from these four groups of six notes (two of which overlap, which would be ロ in Akebono). The tendency to chose one over the other from either half, depends on the context and also on the character of the piece. There are also regional preferences. For example, Kimpū Ryū shakuhachi honkyoku prefers Hon Chōshi to ascend and descend with ツメ:

レ チメ ハ ロ ツメ レ

レ ツメ ロ ハ チメ レ

It also makes extensive use of ツ at ロ pitch, and ロ大メ, which is at the pitch of ハ. So they certainly have a predilection to meri.

Bearing all of this in mind, we really have four scales, if we are to force ourselves to have scales, through the combinations of the four building blocks. To save doing that, for the following recordings I have played the kari option for both halves ascending, and the meri option for both halves while descending.

Listen to each key

Ascending: レ チ大カ ハ ロ ツ レ

Descending: レ ツメ ロ ハ チメ レ

Ascending: ロ ツ レ チ ハ ロ

Descending: ロ ハメ チ レ ツメ ロ

Ascending: ハ ロ大カ ツ レ チ大カ ハ

Descending: ハ チメ レ ツ ロメ ハ

Ascending: チ ハ ロ ツ中 レ チ

Descending: チ レメ ツ中 ロ ハメ チ

Ascending: ツ チメ チ大カ ハ ロ大カ ツ

Descending: ツ ロメ ハ チ大カ レ中 ツ

Ascending: ツ中 レ チ ハ中 ロ ツ中

Descending: ツ中 ロ大メ ハ中 チ レメ ツ中

Temperament

The above audio examples of these keys are tuned to a Just Intonation-based temperament I have created, ‘Senryū I Insempō Temperament’, as an alternative to the 12 Tone Equal Temperament (12TET) based version which is commonly used. This 12TET based system presumably started in or after the Meiji period, due to the dominant influence of 12TET in Japan from Western music since that time, along with the suppression of traditional Japanese music. For example since the Meiji period, Western music was taught from kindergarten upwards, while Japanese music was excluded – a situation which has only started to change relatively recently.

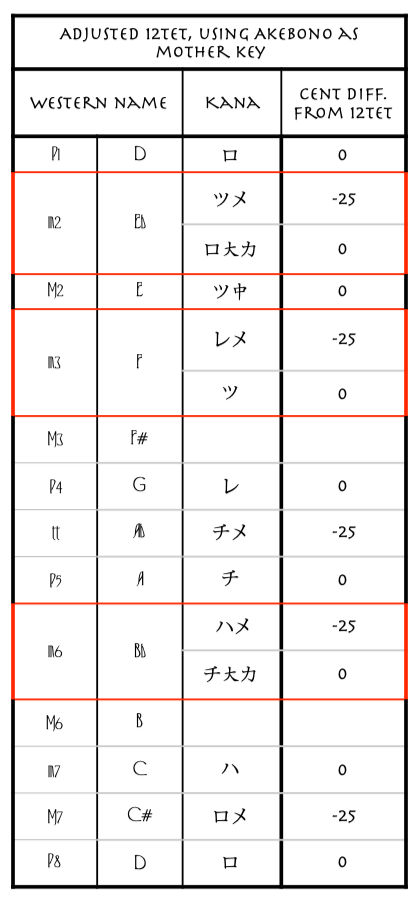

I will now explain the details of that temperament. This will likely only be of interest to music geeks.

Regarding the specific tuning of each note, as I mentioned above, the meri notes are (also in the non-shakuhachi Edo period genres such as shamisen music, koto music and so on) considered to be ‘roughly’ 25 cents flatter than the Western 12TET equivalent. The other notes are generally tuned to 12TET. I call this tuning ‘Adjusted 12TET’. Here is a chart showing the pitch differences for the 13 notes of shakuhachi music according to this system:

This I feel is a compromise due to the lack of any alternative. Since 12TET is definitively out of tune (equally) in every key, as it was designed to be in order to eliminate key change anomalies in piano music, I see no good reason to adopt this Western musical compromise merely because it is common in today’s Western-culture based atmosphere.

12TET was a compromise created for pianos to sound equally out of tune in every key, thus opening composers to the possibility of travelling through many keys in a piece without having to re-tune the instrument. This was preferable to the tunings which gave perfectly in-tune results in one key, but became progressively out of tune the further away from that key one moves.

However traditional Japanese music does use the same scale, and does not have the tendency to travel through so many keys, as Western music does. Rather, shakuhachi music is almost exclusively limited to the four main keys as detailed in this article.

So, if we are to consider what might be a better alternative, I propose the most natural place to start would be to investigate the natural harmonics of the notes themselves. Such intervals based on harmonics are the domain of ‘just intonation’ (JI). These natural relationships are commonly used by people tuning an instrument by ear (including koto); as well as by a cappella choirs, since they naturally sound in tune; and by many native cultures around the world, such as India. Whereas the 12TET intervals are naturally experienced as being out of tune.

A new temperament for old music – Senryū I Insempō Temperament

After being asked by various people around the world to provide some sort of just intonation based shakuhachi tuning by those with a dissatisfaction for the world-dominating 12TET system, I decided to create one, as to my knowledge none existed, the Adjusted 12TET being the only measured tuning/temperament being used aside from pure 12TET.

I have written a detailed paper on the creation of four possible temperaments to solve this problem, and for descriptive convenience I have called these ‘Senryū I Insempō Temperament’ (hereafter referred to as ‘Senryū I’), ‘Senryū II Insempō Temperament’, and so on. Here I will merely provide the results, and then only for Senryū I which is my favourite of the four. Please refer to the more detailed paper if you would like further information on these, and the in depth reasoning behind and advantages of choosing these particular just intervals.

The following chart shows Akebono Chōshi in Adjusted 12TET, and in Senryū I by the number of cents difference from standard 12TET, and for Senryū I also showing the ratio (please read up on Just Intonation if this doesn’t make sense), which represents the note’s natural relationship to the mother note, in this case ロ.

You can hear all keys played on a Edo period jinashi in the above section ‘Listen to each key’. Let’s revisit the scale on a bass. You will thus hear no light and dark tone colour changes, but you can hear the precise pitches, and notice the microtonality differing from intervals of Western, or more broadly non-Japanese music. In music we more usually play ロ ツ レ , and レ ツメ ロ, using the kari note while going up but the meri note going down, for example. See the above section ‘The Four Units of Insempō’ for more on that. Here you will hear the ascending scale with both meri options; then with both kari options; all seven notes ascending; descending with both meri options; and finally descending with both kari option.

In terms of shakuhachi usage, this temperament if achieved, preserves the specific character of the small intervals for the meri notes. However instead of taking the rather randomly round ’25 cent’ interval which may have been originally chosen as simply the roundest number between Western 12TET oriented conceptions of a semitone (100 cents) and a quarter-tone (50 cents), I have made specific choices of natural ratios which produce natural intervals. The ones I have chosen both only stray from 75 cents by a few cents, and combined with the just intervals for the kari notes, produce highly consistent results in Akebono Chōshi. As you can see from the chart, the intervals for the two meri notes are 70.7 and 70.6 cents respectively.

The kari notes are also derived from natural ratios. The results are not many cents away from Adjusted 12TE, but are definitively more natural, coming from the actual harmonics inherent to the nature of vibrating strings and air columns, rather than the mathematical abstractions of 12TET which are designed as a compromise for key shifting issues in an entirely different, Western Classical musical genre.

Key Changes – Complete temperament

This temperament is also well adapted for key changes, giving very little error over the four main keys when the full 13 tone temperament is used, and thus maintaining a far higher degree of naturalness than 12TET or even Adjusted 12TET in every key.

Regarding tuning in the context of shakuhachi making, this only really relates the open holes on the shakuhachi, since the meri notes can be most naturally adjusted by the player when changing keys (which is less the case in practice than adjusting open holes microtonally while playing). However for instruments with more fixed tuning such as kotos (the strings of which are tuned prior to performance and sometimes between pieces), or for other non-Japanese instruments playing music in Insempō, or, for the production of electronic music in Insempō for which nowadays exact temperaments can be programmed, the following complete temperament may be useful. Here are all 13 notes, which thus cover all 7 notes in all 4 keys:

Error rate across keys (for microtonality fans).

This will be of interest to very few of you! For those it does interest, there are more details of the errors of comparative systems in my more in depth paper on this temperament, so I will keep this brief. The whole reason for the existence of 12TET is to minimise errors away from natural or at least consciously desired intervals across keys. It is definitively out of tune, but designed as the best option for making all the keys, on average, as less out of tune as possible. And the rate of error is equal in each key, thus making every key have the same character.

In Japanese music we have different use of pitches than in Western classical or modern Western music. 12TET is very badly out of tune for the ‘meri’ notes, which my temperament also addresses. The added advantages of my temperament are that not only are the notes of Akebono Chōshi giving natural intervals, both for the meri and kari notes; but also, the rate of error away from natural intervals is far less in every key compared to using 12TET. Thus making the key-change advantage 12TE usually has, void. Here is a chart displaying the rate of error for each note, in cents, away from the nearest desirable natural ratio:

Please navigate the menu at the top of the page for more shakuhachi topics, or go straight to this page for more about the history of the shakuhachi and its music; this page for more about the genres of shakuhachi music; and this for more about the honkyoku repertoires of the various regional komusō temples and regions which survive today.